On 24 June, journalist Sophy Roberts posted a video of a group of Batwa children dancing. She wrote: ‘The persuasive innocence of childhood. What this video doesn’t show is the truth of this child’s past and uncertain future.’

Once called Pygmies and historically oppressed, the Batwa were forcibly evicted from Uganda’s newly gazetted national parks in the early 1990s. There was no consideration for compensation by the government at the time. I caught up with Serena Strang, Sophy’s research assistant, to discuss the subsequent survival of a people for whom each day is a struggle against cultural extinction. They encountered a community of Batwa people living along the boundaries of Mgahinga Gorilla National Park, living in a new purpose-built village opened in 2018 by Volcanoes Safaris Partnership Trust.

Described by many people that Serena came across as the guardians and forefathers of the land, the Batwa previously lived in harmony with the mountain gorillas. They roamed the forest for thousands of years, living as nomadic hunter-gatherers and worshipping nature.

Jane Nyirangano, the village leader – a widow with two children, aged nine and four.

It was inevitably the so-called Scramble for Africa – when European interests diced up the land without a second thought given to wild places or those within – that people like the Batwa, and the animals with which they shared the forest, began to be put under pressure from deforestation and habitat fragmentation. ‘When Mgahinga was gazetted in 1991 and the Batwa were forced out at gunpoint, they had no idea how to interact with the modern world – they were just kicked out and expected to deal with it.

‘Many of the Batwa developed alcohol abuse issues. Others struggled to find the motivation to survive – they have found it difficult adjust and some don’t have the will because they’ve lost everything they cared about. It is interpreted by some as laziness or ignorance.’

In 2009, Praveen Moman, who owns Mount Gahinga Lodge (Volcanoes Safaris), started working with the Batwa. Under Moman’s direction, the lodge built a heritage centre where the Batwa could give demonstrations to guests about what their life had been like. Soon after, however, Moman realised that whilst it was keeping their culture alive, it wasn’t doing enough to change their lives as they stood now.

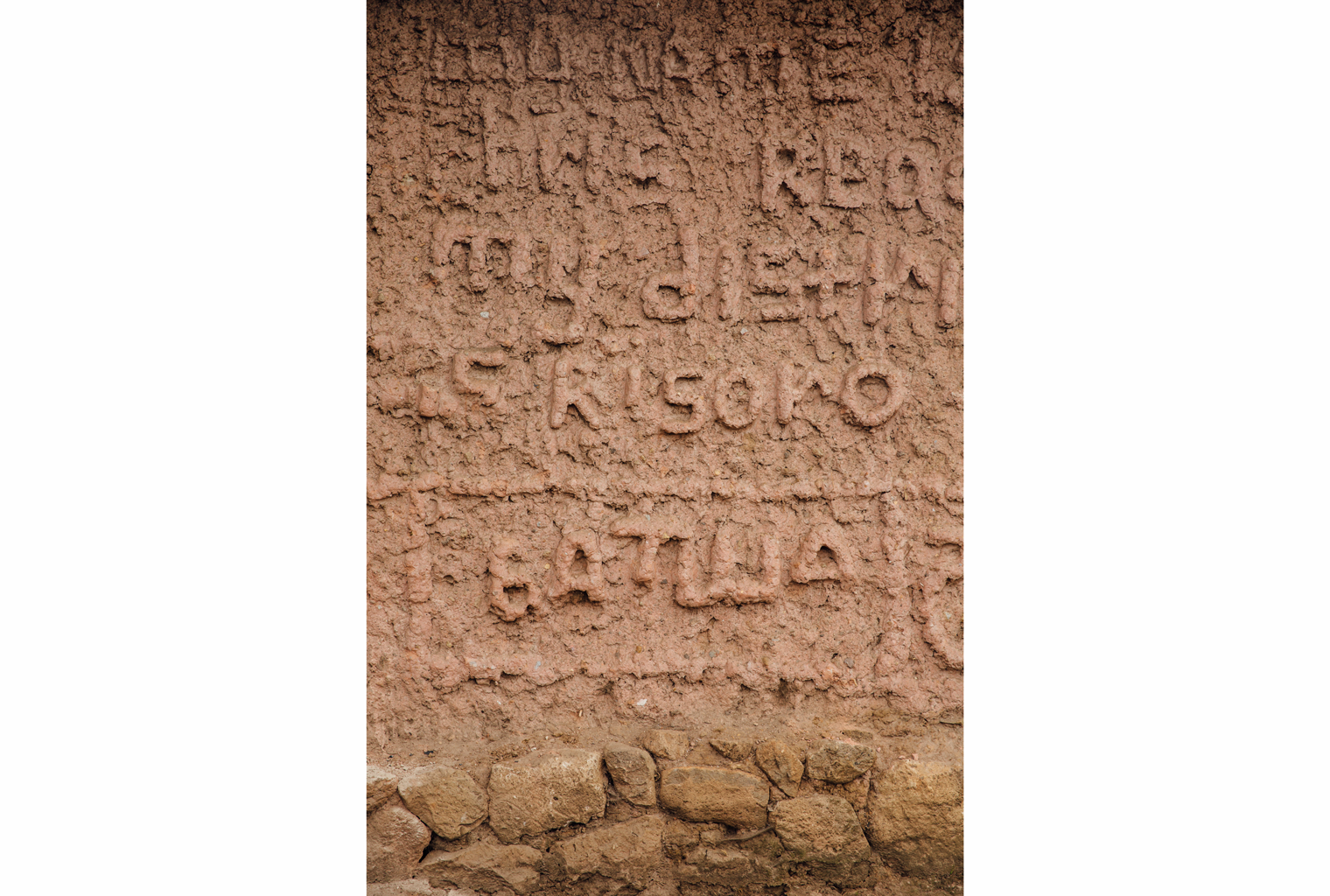

‘The Batwa were asked what it was they really wanted and the response was “We don’t want to pretend; we want houses where we can settle and put down roots.” So, winding forward to 2018, Volcanoes Safaris Partnership Trust – the philanthropic arm of Volcanoes Safaris – built a village for the 109 Batwa who lived in the local area.’

Moman has given the Batwa 13 acres of land and 18 newly constructed homes, as well as a community centre.

With land and property to call their own, the Batwa here are beginning to put down roots.

‘What makes Praveen and the Volcanoes Safaris Partnership Trust special is that they’re not trying to impose what they think is the best life on this community. The village does not come with strings. It’s just about saying: “Here’s the land and the tools. Turn it into what you want for yourselves.”

‘Now a village nurse comes in once a week and sees anyone that’s willing to be seen, administering vaccinations and referring bigger issues to regional hospitals. The Batwa understandably have huge distrust for others, but the nurse coming into the village has begun to build that trust again and it’s laying the groundwork for improved relations with the other local communities.

‘A primary school teacher comes in to run a programme that teaches reading and writing in an integrative manner, raising awareness about alcoholism, hygiene, family planning and HIV. Again it’s optional, but 65% of the adults go.

‘There’s a vocational centre where around 30 of the village women sell baskets and crafts for an alternative source of income. There’s a rainwater tank with 60,000 litre capacity so they can have access to water to boil for clean drinking. The village and its facilities essentially aim to give the Batwa community a space to call their own and the self-pride that comes with that.’

Serena went on to talk about the interactions she had with the Batwa from a tourist’s point of view:

‘It’s not a manicured tourist experience but the welcome is huge. It feels real. The food security isn’t there yet. The Batwa are learning to farm the land but at the moment, live mostly on potatoes, which they call ‘Irish’. The kids have vitamin deficiencies, and there are constant problems with viruses and high HIV levels. It’s not all smiles and rainbows for tourists – this is their real life and it’s a struggle.’

‘The village leader did most of the speaking on behalf of the people. She was proud to be a woman leader pulling her whole community together. She said they had made progress, that thanks to Moman, they have a home now and that is a huge step forward. But there’s still a long way to go. In the evenings, the Batwa sit together and tell stories about what life was like in the forest. It’s a way of keeping their culture alive, although it makes them sad to remember.

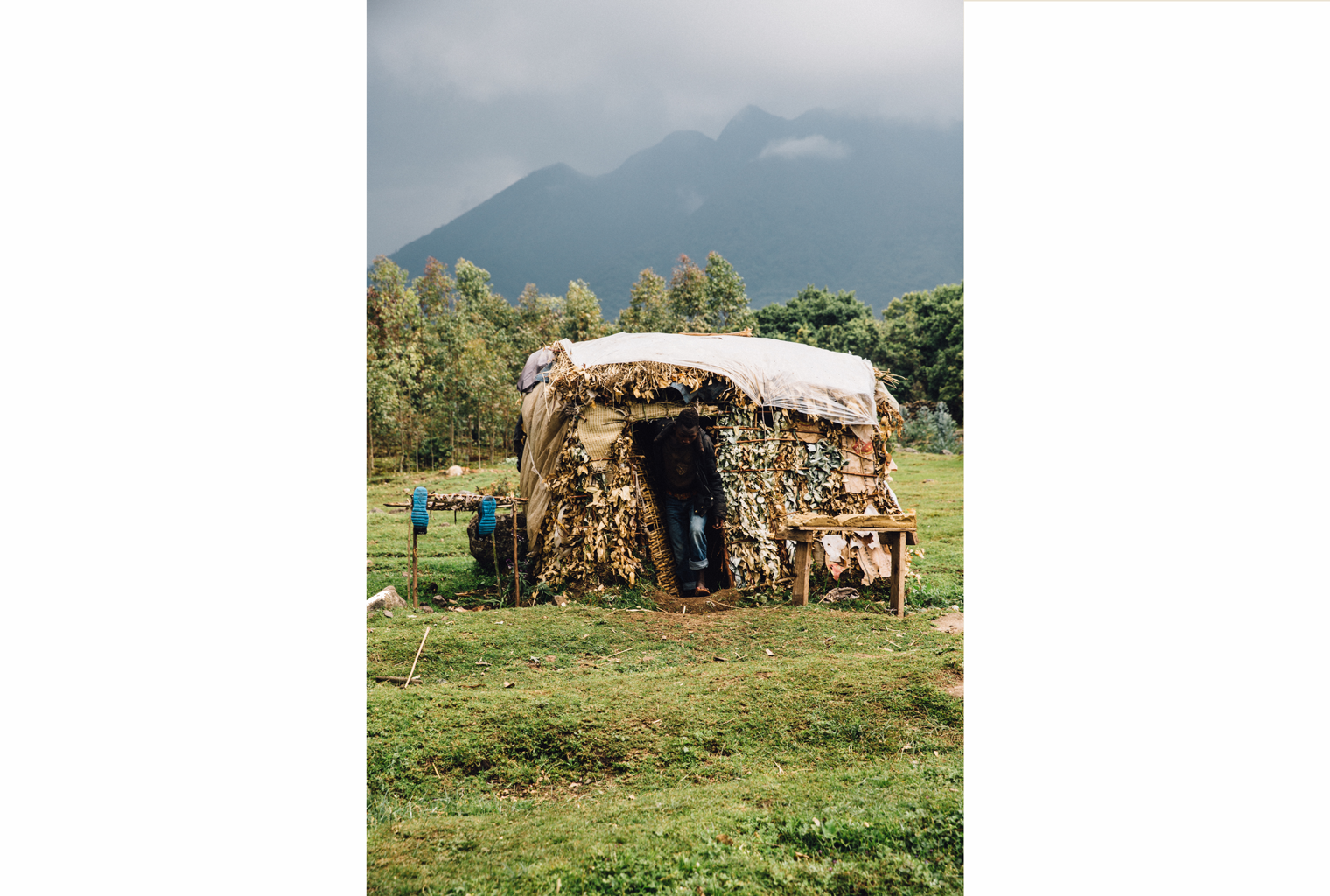

‘A couple of the teenage boys have built themselves a ‘man cave’. The walls are plastered with posters and they hang out there and listen to music. It’s great to think that in any culture, teenage boys slink off to hang out and play music.

A ‘man cave’ built by teenage boys. Behind is Mgahinga Gorilla National Park.

I asked Serena about the underlying motivation of the Batwa for the future.

‘Keeping their culture alive in whatever way they can is important, so traditional dancing is huge – all the children can really move and often everyone does it together. The children learn how to shoot with a bow and arrow even though they can’t hunt anymore. But the Batwa also realise they need to learn to farm. Of course they want their children to remember, but they also want them to have a better life. At the moment, so much of their life is a struggle for survival, it’s almost too soon to be talking about the future.

‘Anyone over thirty remembers the evictions. But for the kids who weren’t alive then, it’s easier to adjust. You have members of the Batwa community going to school and university now, but it will probably be the next generation where you start to see the changes take place, because there is still so much trauma. What Moman and Volcanoes Safaris Partnership Trust is doing here is huge — the community I met had a chance for a future that never could have happened before.’

I don’t want to write this as if it has a Disney ending. It’s early days and there are countless examples across Africa and the world where similar tribes have lost or are losing their cultural heartlands due to increased population and economic development – the Tongwe, the people of the Omo Valley, and the Hadza are all textbook examples of this. There is certainly a glimmer of hope for the Batwa, but for a people for whom existence is a daily struggle, this is just the beginning.

Huge thanks to Serena Strang. For any more information, please do get in touch. Image Credit for all images: Sophy Roberts.